The scientifically accurate representation of the color of the night sky is not a very high priority in the astrophotography community. Most photos of the night sky are edited for aesthetic reasons rather than an accurate representation of the night sky’s color.

Nevertheless, the question of the true color of the night sky and whether it should be a defining factor of the editing process comes up again and again and sometimes leads to heated discussions. I’d therefore like to shed some light on this topic.

The Color of the Daylight Sky

Let me start with a seemingly easy question. What is the color of the daylight sky?

In daylight, the sky away from the sun appears blue, as long as there isn’t excessive haze or cloud cover. Sunlight contains a large range of wavelengths (λ), including those that our eyes are sensitive to. This “visible” range extends from about λ=400nm to λ=700nm. Because nearly equal portions of all visible colors exist in sunlight, it appears almost white. When this white sunlight is scattered by air molecules in our earth’s atmosphere, about 8 times more blue than red light is scattered. The stronger scattering for blue light occurs because the amount of light scattered at each wavelength is proportional to 1/ λ⁴. This scattering by particles that are very small relative to the wavelength of light is called Rayleigh scattering after Lord Rayleigh, who published the theory explaining the blue sky in 1871.

Today, much of the above is considered common knowledge. So why did I write that the question about the color of the daylight sky is ‘seemingly’ easy. That’s because the ‘true’ color of the daylight sky is actually more violet. As the wavelength of violet is shorter than blue, violet light is scattered more. The reason why we see a blue and not a violet sky is that our eyes are much more sensitive to blue light than violet.

While the color of the daylight sky isn’t the topic of this article, we should keep in mind that the spectroscopic color and the color perceived by our eyes (or any other sensor) aren’t necessarily the same.

Sunset Colors

What about those beautiful orange sunset skies? The reason for them, again, is Rayleigh scattering.

Due to the low angle of the setting sun, the light has to pass through much more atmosphere to reach the observers eye. More atmosphere means more molecules to scatter the violet and blue light away. If the path is long enough, all of the blue and violet light scatters out of our line of sight, while the other colors continue on their way to our eyes. This is why sunsets appear yellow, orange, and red.

The Color of the Twilight Sky

Most photographers are familiar with the ‘blue hour’. As the sun moves below the horizon, the golden tones of the sunset are quickly replaced by deep blue hues. The twilight sky is very blue.

Contrary daylight skies, the blue color of the twilight sky is not caused by Rayleigh scattering, though. At twilight, Earth’s shadow prevents light from passing through the troposphere. The light scattered back to Earth’s surface is coming from the stratosphere and above. Due to the shallow angle in which this light passes through the atmosphere, it crosses on a long path through the stratosphere’s ozone layer. Ozone, however, absorbs red wavelengths in a process called Chappuis absorption, leaving only deep blue light to be scattered back to us during twilight.

The Night Sky

Dark night starts when the sun is more than 18° below the horizon. When asked about the color of the dark night sky, it is tempting to say, “black”. That is not correct, though. The night sky looks black to us because there is not enough light to stimulate the color-sensitive cones in our eyes. Nevertheless, there is light in the nighttime sky, and it has color. While we can not see it with our eyes, a camera is sensitive enough to record it with a long exposure. So what is the color of the night sky?

The answer is not trivial, as light pollution, airglow, auroras, and other interfering light sources, like e.g. the Moon, have an impact on the color of the night sky.

Moonlight

Illuminated by moonlight, the sky is blue. The mechanism behind this, as with daytime skies, is Rayleigh scattering of sunlight. The only difference is that the sunlight is now additionally reflected by the Moon.

Light pollution

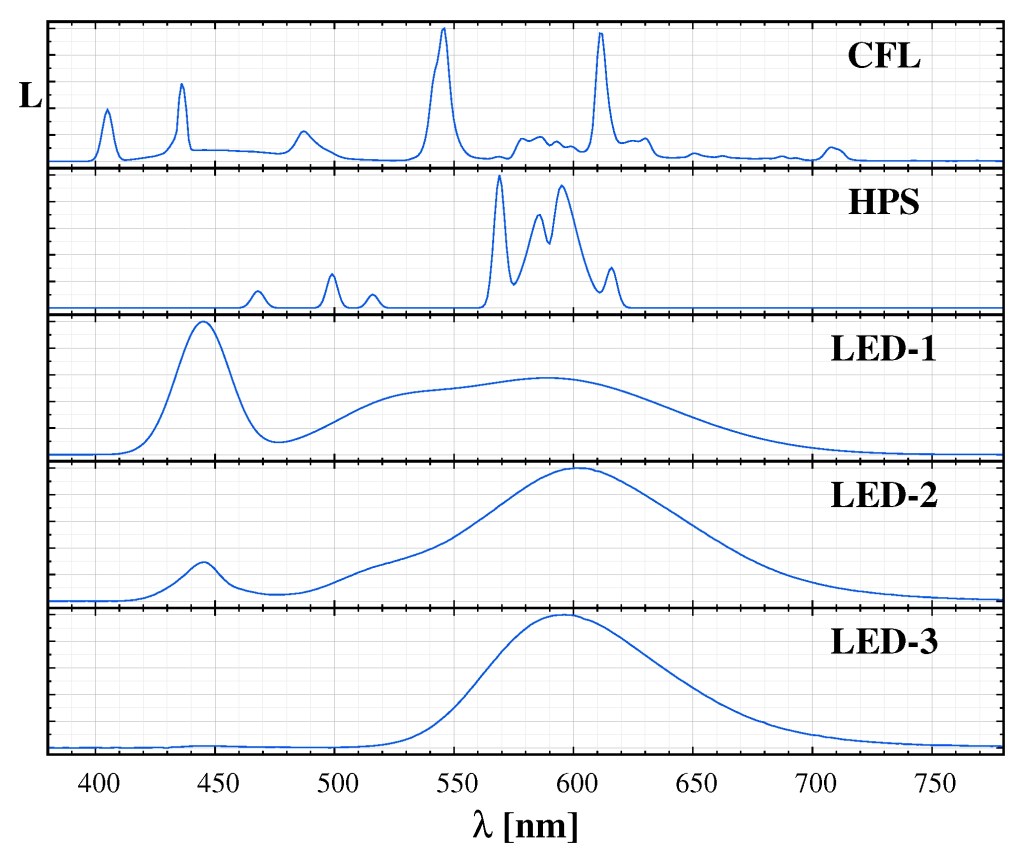

Light pollution also changes the color of the night sky, but the resulting color depends on the source of the light pollution. Old style high-pressure sodium lights cause a distinct orange glow. Cold white LED lights emit a much broader spectrum with a distinctive peak in the blue wavelengths. That’s why they colorize the sky blue. More modern, amber LED lights eliminate the blue light pollution, thus causing again an orange glow, while warm white LEDs are somewhere in between.

The above graph also explains why light pollution filters quite effectively suppress the light from sodium vapor lights but are less efficient with LED lights. Cold white LEDs are the biggest problem, as their spectrum is the broadest, and their peak in the blue wavelengths coincides with the most common wavelengths of starlight and reflection nebulae.

Airglow

Airglow occurs when atoms and molecules in the upper atmosphere, between 85 and 300km above ground, that were excited by sunlight emit light to shed their excess energy. It can also happen when atoms and molecules that have been ionized by sunlight collide with and capture a free electron. In both cases, they eject a particle of light, a photon, in order to settle down on a lower energy level. The phenomenon is similar to auroras, but while auroras are driven by high-energy particles originating from the solar wind, airglow is energized by ordinary, day-to-day solar radiation.

Unlike auroras, which are episodic and fleeting, airglow constantly shines throughout Earth’s atmosphere, and the result is a tenuous bubble of light that closely encases the entire planet. Just a tenth as bright as all the stars in the night sky, airglow is far more subdued than auroras, too dim to observe easily except in orbit or on the ground with clear, dark skies and a sensitive camera.

Image credit: NASA

Each atmospheric gas has its own favored airglow color depending on the gas, altitude region, and excitation process. After extreme solar activity, like high extreme UV radiation, the level of airglow can increase by a factor of 5–10. Airglow emission is also affected by atmospheric conditions, like gravity waves, which can give airglow pronounced structure.

The starlit night sky

But what is the color of the night sky in the complete absence of added artificial or natural light sources? ESO has made an extensive study about this for the site of the Very Large Telescope at Cerro Peranal in Chile.

The result may be surprising for most: Contrary to the usual impression of bluish or neutral grey night skies, the color of the night sky really is in the orange to green range. Blue color only appears during twilight or with moonlight.

Image Processing

Most landscape astrophotographers, including myself, put a lot of effort into showing the sky in the scientifically correct position over their landscapes. Images where the sky was moved for compositional or other reasons are frowned upon as digital art, not photography. It is, therefore, logical to assume that we also strive to show the real colors of the night sky. This is not the case, though. Why?

As mentioned, the human color vision is not working under very low light at night. Humans simply can not see the real color of the night sky. That’s why our gut feeling of how a night sky should look is based on other images we have seen and our daylight experience, rather than the scientifically correct color shades.

Furthermore, the “true” color of the night sky at any given time and place is very difficult to determine. Camera sensors are not calibrated for consistent color reproduction, and there are very few places with absolutely pristine sky conditions, and even there, the color is not consistent due to the ever-changing airglow.

Most photographers, therefore, process the night sky to their and their customers’ artistic tastes rather than with scientific precision. While most deep space imagers process their images with neutral gray backgrouds, many landscape astrophotographers, including myself, seem to prefer a slightly bluish hue.

Even though many are aware that this isn’t scientifically correct, there are good reasons for these seemingly arbitrary choices. As we are used to seeing blue skies during daylight and twilight, we seem to prefer a slightly bluish hue in landscape astrophotography images, too. All landscape astrophotographers I have talked to, confirm that images with bluish skies get more attention and sell better than images with a more scientifically correct white balance.

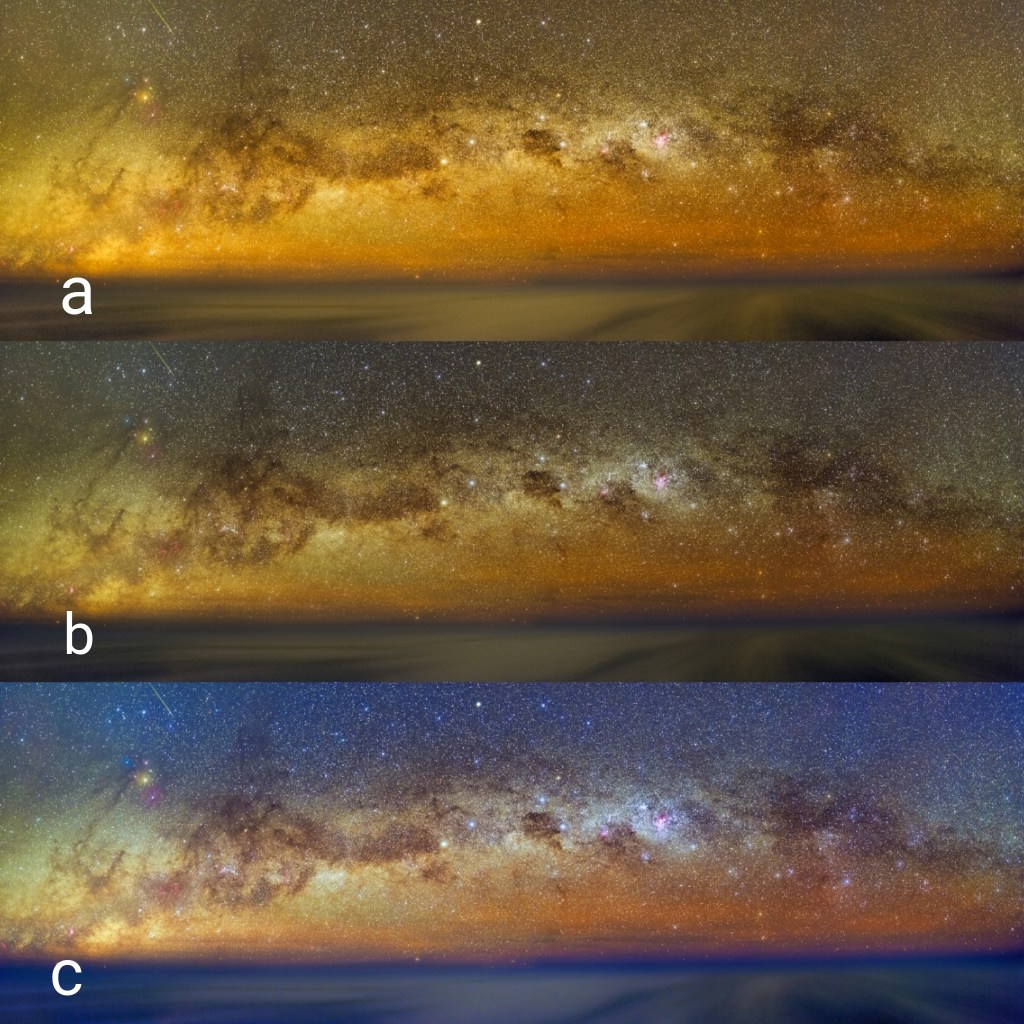

Another reason for choosing a slight blue or neutral color balance is that we enhance our astrophotos to emphasize the structures and to obtain more vivid colors. The example below shows that a bluish hue makes the red hydrogen emission nebulae stand out better than a warmer, orange color balance.

(a) approximately correct sky color

(b) white balance for neutral sky background

(c) a blue color balance emphasizing the pink hydrogen emission nebulae.

The same is true for airglow, which also more vividly with a neutral or slightly blue sky, and the cooler color balance also corresponds better with what we consider natural looking foreground colors.

Common Mistakes

Although there is a lot of artistic freedom to astrophotography processing, there are some common mistakes that I think should be avoided.

Many beginners process their Milky Way images extremely blue. While that’s fine from an artistic viewpoint, an overly cool white balance kills the subtle hues of the night sky instead of enhancing them. I have seen images that, despite being captured with an astro-modified camera, were completely void of pink tones due to a ridiculously blue white balance.

The example below shows how the subtle hues of the night sky can be destroyed by a far too blue white balance.

Another mistake I see quite often is a sky with a considerably pink hue. I am not sure why some astrophotographers process their images this way, but a pink sky looks weird to me, as it is very far from the true color of the night sky. But a pink sky not only looks counter-intuitive, similar to an overly blue processing, it also hides the natural nuances of the night sky.

Conclusions

Astrophotography is science inspired art, but not science. Some astrophotographers seem to forget this and confuse their personal tastes and processing ethics with absolute scientific truth. There is a lot of artistic freedom in processing astrophotos, which is a good thing.

We use modified cameras to capture more light in a specific wavelength and we use filters to suppress the wavelengths with the worst light pollution. During post processing, we increase contrast and saturation and stretch our images non-linearly to reveal subtle structures in the night sky. Images are sharpened with complicated mathematical formulas. Data captured with sophisticated narrowband filters are added to reveal even more structures and light pollution gradients are reduced or even completely removed with complex processes. Satellite and aircraft trails are removed with outlyer rejection algorithms. All this is accepted as part of the astrophotographer’s workflow.

Most of the above techniques alter the data in a scientifically unacceptable way. To make it clear: A standard astrophotography contains little scientifically usable data. From the uncalibrated sensors we use in our cameras to our post processing techniques, everything is pretty unscientific. The times when astronomers analyzed images are also pretty much gone. Today, astronomers are mainly crunching numbers. The awesome images we see from the bilion Dollar Hubble and James Webb telescopes are made for public outreach. While the data that went into those images were captured with a scientific purpose, the images themselves are basically just a tool to convince the tax payers that their money is spent wisely. For scientific research, they are irrelevant. These images are produced with the same unscientific post processing techniques we amateurs use. The laughter in the astrophotography community was pretty loud when the first JWST images were published and we found that they were processed by some selected amateur astrophotographers with our favorite astrophotography processing software, PixInsight. In hindsight, that was no surprise though. After all, professional astronomers do not usually process images. The guys that can do this best are the leading amateur deep space imagers and, of course, they work with the techniques and software they are used to.

What I am trying to say is that absolute scientific accuracy in astrophotography is a myth. We do not aim to do science, we are photographers who want to produce beautiful images that reveal structures and colors of the night sky that would otherwise be invisible to the human eye. The word ‘beautiful’ is important in this context. There is no point in producing ugly, counter-intuitive looking images just to stay a bit closer to the mythical scientific accuracy.

I do not understand this as a free pass for any form of digital image manipulation. As mentioned above, I still think it is important to show the sky in the scientifically correct position and size over my foregrounds. The challenge of finding, calculating and capturing a good alignment is an important part of the fun in landscape astrophotography.

Nice article but a couple corrections: Visible light starts around 400nm, not 525nm. And wavelengths shorter than blue are ultraviolet, not purple.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your valuable input! You’re absolutely right about the lower wavelength of visible light. I corrected the mistake. You are also right about the color purple, which is a mix of blue and red. I corrected the text to violet, as ultraviolet, according to my information, is used for the invisible wavelengths below 400nm.

LikeLike

While it is true that we astrophysicists are primarily interested in linear, properly calibrated flux data, and most don’t have the skills to produce more artistic photos, there absolutely is scientific, not just PR value in the images produced by astrophotographers. They help us to better see and appreciate what is in the images. I have several times been inspired to write a paper based on amazing astrophotos that reveal something new or inspire a new interpretation of phenomena in a familiar galaxy or nebula. Keep up the great, inspiring and artistic work. It moves us all towards more wonder and discovery.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for the nice comment. I often say inspiring others to start with astrophotography is my greatest reward. If I can inspire somebody to pick up a scientific career or write a scientific paper, that’s even a greater reward though.

LikeLike