If you follow my photography, you certainly have seen them. Sweeping panoramas with the Milky Way arching trough the sky. Is this arc real or just an artefact of panoramic projection?

This question seems to cause a lot of confusion. If you Google it, you find many answers that, while not totally wrong, aren’t entirely correct either. So let’s discuss this topic a bit deeper.

What is the Milky Way?

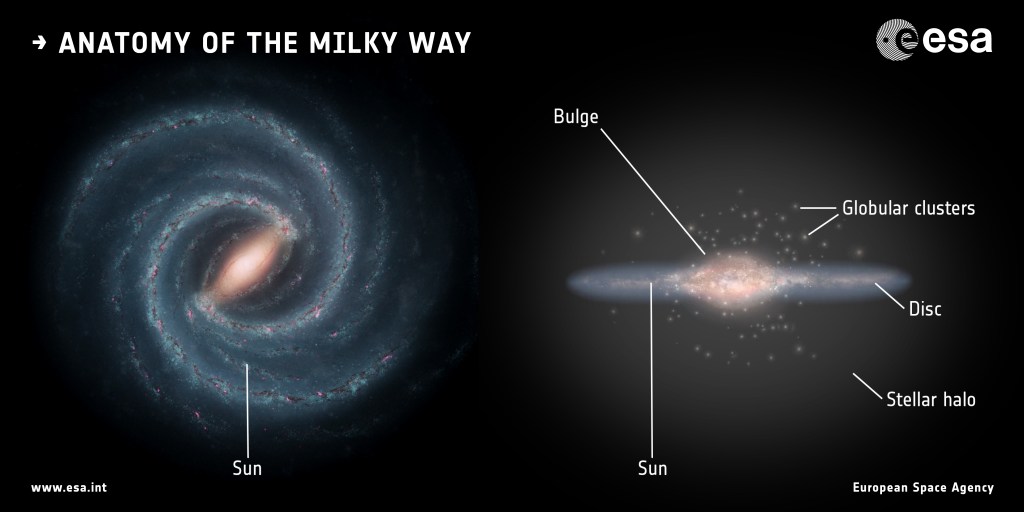

The Milky Way is our home galaxy. It is ‘barred spiral galaxy’ that is home to a few hundred billion stars, including our Sun.

Right: An edge-on view reveals the flattened shape of the disc. Image credit: ESA

The above image shows that the Milky Way forms a flattened disc. Most of its mass is concentrated near the galactic plane. The solar system sits embedded in the Milky Way, about halfway between its center and the periphery, but almost exactly in the galactic plane. The Milky Way, therefore, surrounds us. Actually, all stars in our night sky are part of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Most people, however, do not think of a galaxy when they hear ‘Milky Way’. Those who are not reminded of the famous chocolate bar will most probably think of the milky band of light visible to the naked eye from a dark area at night. That’s where our home galaxy, the Milky Way, got its name from. In order to avoid confusion, let’s call this band the Milky Way Band.

What is the Milky Way Band?

The Milky Way band is the combined light of millions of stars that lie in the galactic plane of the Milky Way Galaxy. These stars are too far away from Earth and too densely packed for our eyes to be able to resolve them individually, but we are able to see their combined light as that milky glow in a night.

As we are sitting within the galactic plane, the Milky Way Band surrounds us like a circle. If we watch the sky perpendicular to the galactic plane, we look towards the galactic poles. There still are many stars in that direction, but not nearly as many as in the galactic plane. The brighter ones appear as individual points of light, but there is no combined glow in the direction of the galactic poles.

The shape of the Milky Way Band

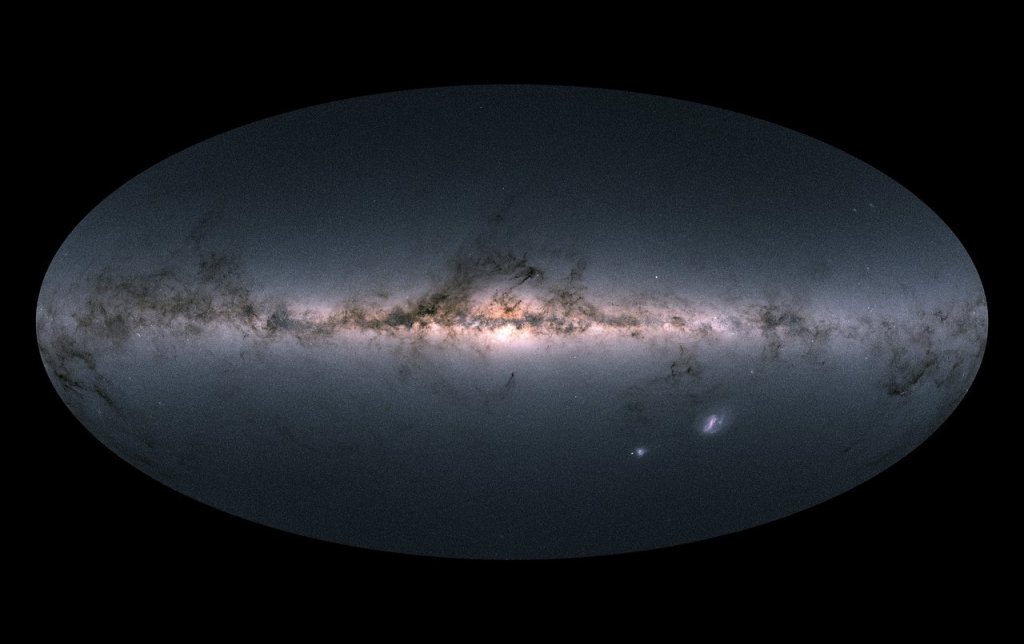

The above image, captured by ESA’s Gaia satellite, depicts the Milky Way Band as a straight line. Of course, this is entirely correct: When viewed from the inside, a circle appears as a straight line surrounding the observer.

Now, why does this straight line appear as an arc or bow in Milky Way panoramas captured from Earth? This is where the confusion starts.

As mentioned, you can find different answers to this question. Most images with Milky Way arcs are panoramas and consequently, the most common explanation blames panoramic projection to distort the sky in the final images. Let’s look at this a bit closer.

Panoramic Projection

When seen from the surface of our home planet, the Milky Way Band spans roughly 180° of the sky. Except with fisheye lenses, it is impossible to capture such a huge field of view in a single image. Therefore, astrophotographers capture panoramas to image the whole Milky Way. When shooting a panorama, we do not extend the field of view by moving the camera sideways. Instead, we turn the camera on the tripod. Consequently, we are recording the inside of a curved sphere, a spherical panorama.

As all our displays and photographic prints are flat, we have to find a way to display a curved sphere on a flat medium. This requires projecting the spherical panorama on the flat plane. There are different ways to do that, but all of these projection methods cause distortions and some of them bend straight lines into curves.

For a few Milky Way panoramas, like the example below, panoramic projection is indeed the cause for the Milky Way Band to appear as an arc.

The above image covers a horizontal field of view of roughly 340°. While recording the image, the Milky Way Band formed a straight line from one side of the horizon to the other. In order to display this spherical panorama on a flat surface and to make the horizon straight, the whole image had to be distorted, resulting in a seemingly arching Milky Way Band.

Lens Distortion

Lens distortion can also make a straight line appear as a curve. This is especially true for fisheye lenses, where only lines going exactly through the center of the image remain straight. Some astrophotographers use fisheye lenses to record a wide enough field of view to cover the entire Milky Way band in a single frame. Instead of having to turn the camera to record a spherical panorama, the bulbous glass of a fisheye lens is able to record the spherical panorama in a single frame. The camera sensor is still flat, though. Therefore, the problem is the same as with a panoramic projection. A fisheye image is the projection of a sphere on a flat surface, too. The only difference is that fisheye achieves this projection optically, while the panoramic projection is a digital process during panorama stitching.

Problem solved?

This is where most explanations stop. Problem solved! Thanks for reading – well, not quite.

Every stargazer, who has seen the rising Milky Way Band in spring, can confirm that it forms an arc in the sky. These arcs are real! The starry arcs in images showing the rising Milky Way Band are not the result of panoramic projection or lens distortion, as these arcs are visible with the naked eye!

How is this possible, when we know that the Milky Way Band encircles us in a flat plane? The answer is a bit complex and has nothing to do with photography.

The Celestial Sphere

You certainly have heard the expression ‘celestial sphere’. No worries, it is not getting esoteric here. I am talking about what Encyclopedia Britannica describes as “the apparent surface of the heavens, on which the stars seem to be fixed”. The celestial sphere is how an observer perceives the sky around him. Everything that we see in the sky is projected onto the celestial sphere.

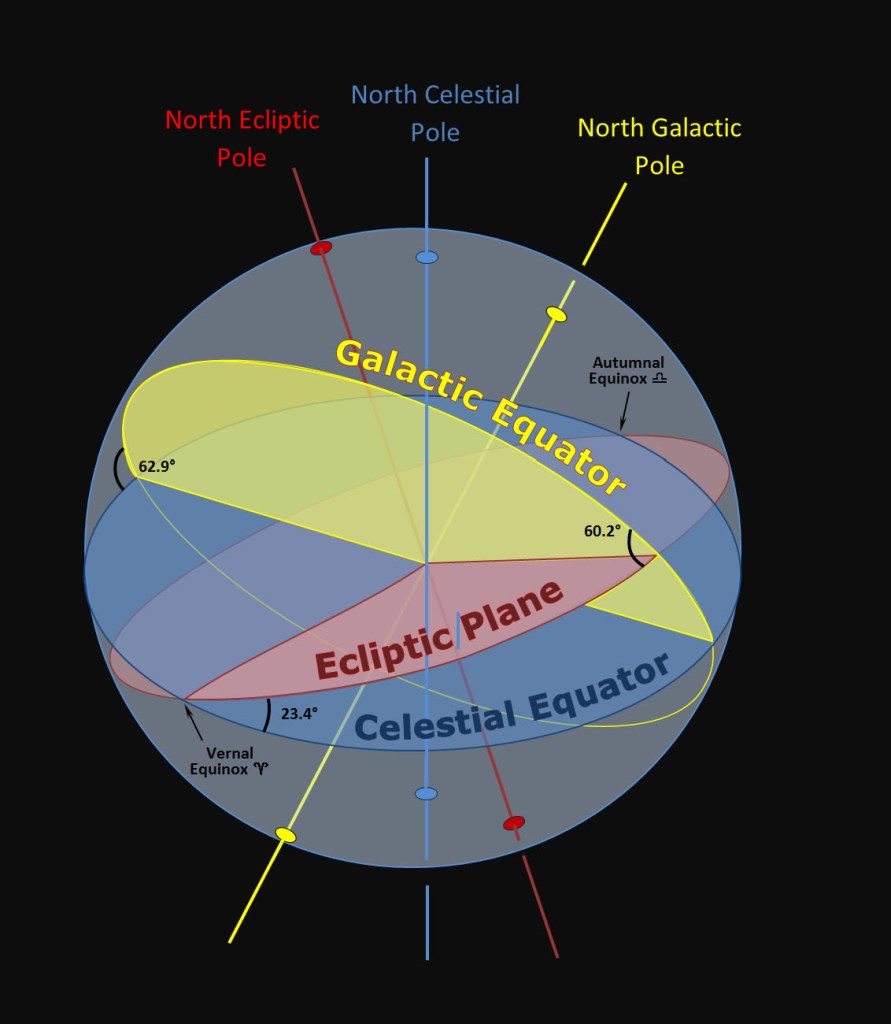

This not only includes the stars. The Celestial Equator, for example is the projection of Earth’s Equator onto the celestial plane. Consequently, the Celestial Equator is the dividing line between the northern and southern hemisphere on the Celestial Sphere.

The Celestial Sphere also includes the appareny yearly path of the Sun through starry sky. This path is the intersection of the Ecliptic plane, the plane in which Earth circles around the Sun, with the celestial sphere.

Finally, the Galactic Equator is the intersection of the galactic plane with the celestial sphere. It actually corresponds with the Milky Way Band.

The Ecliptic Plane, the Galactic Plane and the Celestial Equator meet in the position of the observer, at the center of Celestial Sphere. The intersections of these planes with the Celestial Sphere form great circles.

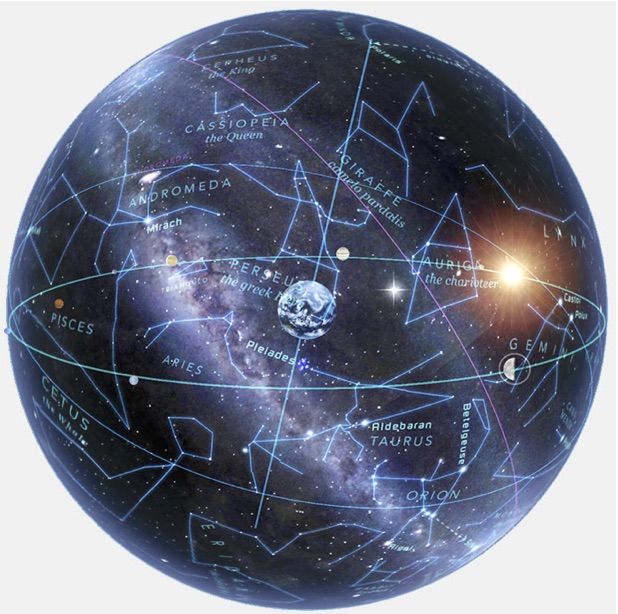

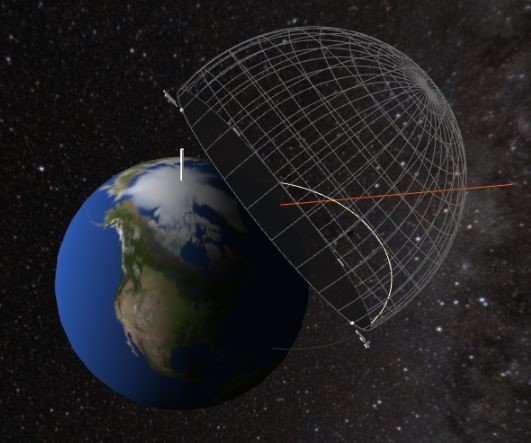

The image below shows that the Milky Way Band forms a geat circle on the celestial sphere. Similar to Earth in the center of the image, an observer who is free-floating in space, will see the Milky Way Band as a flat circle surrounding him.

The Local Horizon

As earth based observers, however, we can never see the entire celestial sphere. We perceive the night sky as a half sphere or dome extending above the plane of our local horizon. To make things even more complex, the local horizon is tilted at an angle depending the latitude of the observer (90° – LAT). Fortunately, this tilted horizon does not affect the topic we are discussing here.

A local horizon, however, changes things compared to a free floating observer in space. All great circles seen from within a half sphere, except those that pass directly overhead, appear as arcs over the local horizon!

That’s the true reason why the Milky Way Band forms an arc in the sky, except when the Milky way is standing vertically! Heureka!

The Stellarium screenshot below shows the rising Milky Way Band at a mid northern lattitude in spring. The Milky Way Band intersects with the local horizon in the North. It then rises to its highest altitude in the East and drops again to meet the local horizon once more in the South-East.

This obviously results in an arc spanning almost 180° in the sky, exactly as it is depicted in many Milky Way panoramas. This arc is not caused by lens distortions, photographic processing or panoramic projection. Despite the fact that the Milky Way galaxy surrounds us in a flat plane, the arc is 100% real.

There is a little experiment that can visualize this. All you need for this is a hula hoop. If you hold your head inside the hula hoop and tilt it compared to the the horizon, it will form an arc in the sky. Only if you hold the ring vertical or horizontal it will appear as a straight line.

Therefore, the answer to the question in the title of this article is:

The rising Milky Way Band appears as an arc to an earth based observer, because it is projected on the celestial sphere, resulting in a tilted great circle above his local horizon.

Fascinating! Lots of awesome info there..Really appreciate 😃

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much, Cindy!

LikeLike