Lately, quite a few Milky Way images that were taken from airplanes have been popping up in social media. Nevertheless, many people are still astonished that it is possible to capture the Milky Way from a fast moving airplane without star trails. It is therefore time to look a bit deeper into the topic.

“Towards the core”

5s @ ISO6400 for the sky and 20s @ ISO1600 for the grond – f/1.4

“Colors of Cygnus”

Single exposure: 5s @ ISO6400 – f/2

“A Job with a View”

Single exposure: 5s @ ISO6400 – f/1.4

Professional Airborne Astronomy

The concept of airborne astronomy is not new and has been applied by professional astronomers since 1957, when Stratoscope 1, a high flying helium balloon equipped with a 12 inch telescope took high resolution images of the sun. Later, the focus shifted to infrared, UV, microwave, Gamma- and X-ray astronomy, as these electromagnetic frequencies are blocked by the dense lower atmosphere.

In 1965 the first telescope was mounted on a jet aircraft. The NASA Galileo Airborne Observatory used a converted Convair 990; destroyed in 1973 in a mid-air collision. It was followed in 1974 by the NASA Kuiper Airborne Observatory (KAO) on a Lockheed C-141A Starlifter that operated until 1995.

The NASA Kuiper Airborne Observatory (KAO)performed airborne astrophotography for over 20 years. Photo courtesy NASA.

NASA’s last airborne observatory saw first light in 2010 and was called Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA). It was an 80/20 partnership of NASA and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and operated an extensively modified Boeing 747SP aircraft carrying a 2.7-meter (106-inch) reflecting telescope. SOFIA was decommissioned in Srotember 2022.

As these professional instruments prove, it is possible to do astrophotography out of a flying jetliner, but why is this possible without producing star trails? Let us look into this:

Linear Motion is Irelevant

Typically, jetliners cruising speeds are around 80% the speed of sound (Mach number: M 0.8). At 15°C (59°F) and sea level pressure, this is 272 m/s (980 km/h, 609 mph). As the speed of sound depends on temperature and as the temperature is much colder at the cruising level of an airliner, this figure drops to about 240 m/s (850 km/h or 530 mph) at 10’000 m (33’000 ft). To make things even more complicated, you have to add the wind into the equation. Wind speeds at this height can easily reach 300 km/h (180mph). To get the speed over the ground, you have to add the tailwind or subtract the headwind from the true air speed derived from the Mach number. In a strong tailwind an airliner can therefore reach ground speeds of about to 1150 km/h or 700 mph.

This is very fast, but it is only about 1% of the 107’000 km/h (64’850 mph) at which earth is moving around the sun and not even this velocity is causing star trailing, because the stars are very far away. In other words: As long as you do not fly with warp speed, linear motion is irrelevant.

Did I loose you there? No worries. A little thought experiment helps to understand this:

Let’s imagine we are on a train journey through a full moon night. Our gaze wanders through the window to the landscape flooded with bright moon light. Nearby objects, such as catenary masts, whiz past our window in fractions of a second. The lights of the nearby houses are only visible for a few seconds. The distant hills, however, roll past us at a leisurely pace and the bright moon seems glued to its place in the window. The reason for this is the different distances of these objects to us. As long as we are driving straight ahead, an object in our window will move less and less quickly as the distance increases. Objects at infinty, like e.g. the stars, wont move at all.

What Causes Star Trails in a Long Exposure?

Star trails are caused by angular motion, i.e. the rotation of your camera or your mount. But you are using an extremely stable tripod and still get star trails after a few seconds, right? That’s because your tripod is standing on a huge rotating base called Earth, which rotates 360° in 24 hours. To take long exposures without star trailing you must therefore either limit your exposure time or you have to use a tracking device that counters earth rotation.

An Airborne Tracking Mount

So all is good and you just have to set up a tracker on your next long-haul flight and you can expose virtually forever? Not quite.

An aircraft is not flying in a straight line; it follows the curvature of earth. If you are flying westward, the speed of the aircraft therefore counters the effect of earth rotation, while flying eastward makes things worse. But how do the rotational velocity of earth and the speed of an airliner compare? With its circumference of 40’000 km (24’900 mi), the equator rotates with 1670 km/h (1038 mph). This figure decreases with increasing latitude, as the circumference decreases to 0 at the pole. Mathematically the rotational velocity is the cosine of the latitude multiplied with the speed at the equator.

At mid northern or southern latitudes, earth rotates at almost the same speed as the typical ground speed of commercial aircraft. This is the reason why, on a westward flight, you land at almost the same local time as your time of departure.

So you can even leave your tracker at home, because the aircraft acts as an airborne tracking mount on westbound flights, while you better get some sleep on eastbound routes? In theory yes, but unfortunately reality makes things a bit more complicated again.

What Limits Airborne Astrophotography?

Most people are well aware that camera shake destroys any astrophotography. Unfortunately even a 300’000kg flying camera mount is not totally stable. In addition to hand-holding your camera, there are two main causes for camera shake in an airplane:

Turbulence

Turbulent air causes short term non-linear motion of the aircraft. Even if you managed to fix the camera to the aircraft structure, this makes the stars jump around in your image, causing erratic trails or blurred stars.

Dutch Roll

Dutch roll is a type of aircraft motion, consisting of an out-of-phase combination of “tail-wagging” (yaw) and rocking from side to side (roll). Swept wings of commercial transport aircraft tend to increase the Dutch roll tendencies. This yaw-roll coupling is normally well damped by the installation of a yaw damper, but it nevertheless causes a slight motion of the stars in a long exposure. Dutch roll is most pronounced when shooting out of a side window and, depending on its strength, it can cause stars to appear as doughnuts instead of points.

An exposure taken in perfectly still conditions appears blurry when zoomed out and a 100% crop reveals doughnut shaped stars, caused by aerodynamic oscillations (dutch roll).

Exposure time therefore is normally not limited by conventional star trailing, but by the rocking and rolling motion of the aircraft. Even though you may be sitting in a flying tracking mount you have to keep your exposure time as short as possible.

Too much Glass

For astrophotography I recommend to have as little glass in the light path as possible. In other words: get rid of all your filters! For airborne astrophotography however, you will hardly have the privilege to have an open a hatch available, like in those professional flying observatories. Depending where you sit, you will therefore be shooting through thick of glass or even some plastic. This not only can introduce distortions, but the windows are also very prone to reflections, especially because you will always have some light in the cabin. There are two ways to try to avoid this:

– You can make a total fool out of yourself and hide under a blanket. This works surprisingly well but your fellow passengers might consider your behavior extremely suspicious. I therefore strongly suggest informing your neighbors and the cabin crew about what you are planning to do. Furthermore, you better dress lightly, as it can get rather stuffy in the long run.

You can use a lens skirt. This is a flexible hood which you attach to the end of your camera lens and on the other side to the window with suction cups. This lets you breathe better and does not nearly look as silly as the blanket.

Strobes and Beacons

Most astrophotographers do not especially like aircraft trails. These trails are produced by the strobes, beacons and navigation lights and they can be an even bigger nuisance when shooting out of the aircraft. Unfortunately you cannot simply ask the pilots to shut down all these lights, as they are important for flight safety. You therefore have to live with them. The red and green navigation lights on the wing tips are normally not a problem and the strobe lights can even have a nice effect. The biggest challenge is the red beacon light which tends to cast an ugly red hue. Fortunately, this can be corrected in post processing or you can also try to use the light for something creative.

Single exposure of 5s @ ISO6400 – f/2

Stabilizing the Camera

You are certainly aware that it is not best practice to hand hold your camera for long exposures, but if you have no other option, you might as well give it a try. In this case, try to press your lens to the window and operate your shutter with a self-timer or a cable release.

A better solution is to use a tripod to properly position your camera, but depending on how tightly packed the seats are, you might have a hard time to set it up.

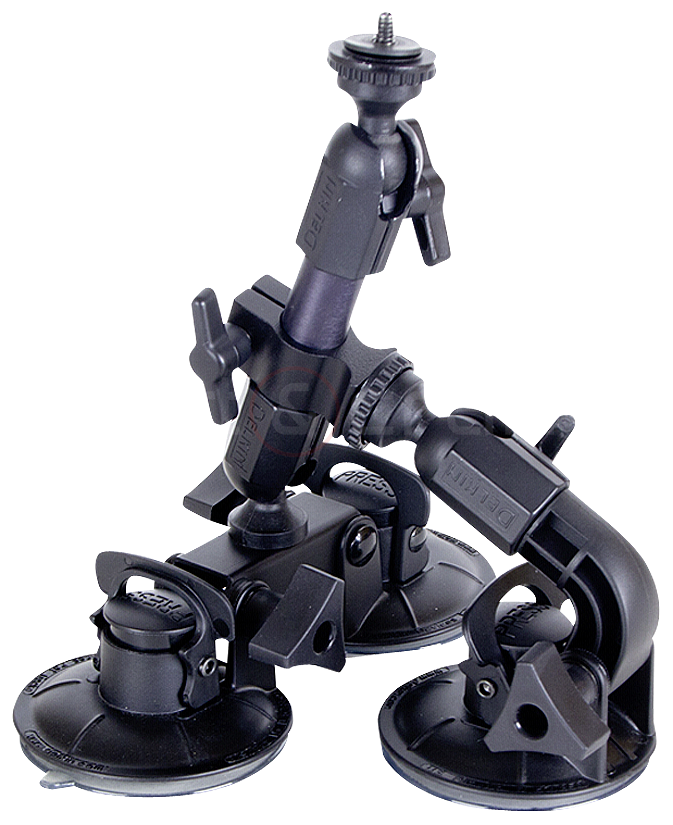

My preferred way therefore is to use a Delkin FatGecko suction mount. There is a huge selection of different models with one, two or three legs. Of course I have the privilege to have big windows in the flight deck, but with the larger cabin windows of the new generation of airliners, you might be able to install one of these in the passenger cabin as well.

Dreamliner Dreams

One word of caution: Boeing’s new 787 Dreamliner not only ditches classic small windows with pull-down plastic shades and replaces them with large, dimming windows that can be adjusted to let in various amounts of light. These windows can be individually controlled by the passengers, but the flight attendants can also change entire sections of the plane. I know that certain airlines are remotely dimming all windows during night flights to avoid stray light entering the cabin. You may, therefore, have to convince your cabin crew to give you control over your window.

Recommended Technique

As mentioned above, you will have to keep your exposure time as short as possible. A fast lens will help you to gather as much light as possible in the short time available, but you will also have to increase your ISO as high as practical. I use a 24mm f/1.4 prime lens and normally expose for 5sec @ ISO6400. Depending on your lens and camera you will have to adapt these settings, but try to keep exposure times short.

Nevertheless, most of your images will inevitably be blurred. In reasonably smooth conditions, I normally get about 2 – 5% sharp exposures. This means that you’ll have to acquire a long sequence to ensure that you get a few keepers.

High ISO Comes With A Price

High ISO shooting comes at the price of increased noise. As in terrestrial astrophotography, stacking several exposures helps to lower these noise levels. Unfortunately, it is much harder to get a sequence of clean exposures for stacking from an airplane, but as you will capture a long sequence anyway, check if you have several good shots that can be stacked. For this you only need the exposures to be sharp, as you can align the stars with specialized software like Sequator (PC) or Starry Landscape Stacker (MAC).

If the conditions are too turbulent for stills, consider capturing an extended sequence, and make a time-lapse movie. The high frame rate and the lower resolution of a video will hide much of the blur in each individual frame, and fast-moving lights and clouds guarantee a stunning sight.

Time Lapse Movie captured during a flight from Zurich to Sao Paulo.

Just the Milky Way?

As in terrestrial nightscapes, the Milky Way is the most prominent target, but there are other interesting things out there. Northern lights, thunderstorms or constellations can keep you shooting on every night flight without the need for on board entertainment.

Milky Way over Brazil

Give Airborne Astrophotography a Try

Take your camera and have fun on your flights! I wish you a smooth ride.

Beautiful read. I loves physics in school so this makes sense to me. Going to Alaska in 7’days maybe i will give it a try

Shuping from VERO

LikeLike